In a world where attention spans have been reduced to seconds, college students aren’t expected to read full books, AI is used to summarise anything more than a few sentences, and blogs have been largely replaced with microblogging platforms, is there still a place for long-form writing? In this essay I would like to explore that question; from how we got here to what hope we have for the future.

This is a complex topic, and to properly explore this, we need to go back several decades. What we see today are the symptoms of decades of changes and issues, layered one upon the other, building up to a far larger issue than what any of these could explain in isolation. While this essay goes on quite a journey, I believe that the journey is worthwhile and enlightening.

Before we truly begin, I must confess an important fact: despite the length of this document, the countless hours that have been spent in research, writing, and building up to this essay, the question it presents won’t be answered. While I intend to explore the question in detail, I won’t provide the answer. In reality, I don’t know. Long-form writing, as we know it, may be a dying art.

We start at the start, which is to say, how we learn to read. If you are not familiar with the three-cueing method, I suggest you read this, as this is critical to our analysis. If you are familiar, feel free to skip ahead.

Since as early as 1570, children in the English-speaking world have largely learned to read through a system that’s now called phonics. A system that focuses on the sounds associated with the letters & letter groups, allowing new readers to break down words into smaller components and work through those components individually. Phonics has strengths and weaknesses; it allows a reader encountering a new word to work through it to discover what it is with some effort. It’s also slow to show progress and frustrating for those learning to read.

In the 1960s, a new method was introduced that aimed to simplify learning, and allow new readers to achieve literacy faster. Three-cueing doesn’t focus on breaking words down to understand them, but using context clues to allow readers to make guided guesses1. This system taught readers to look at three elements to identify context.

When a reader encounters a word they aren’t familiar with, they are taught to look for the following cues to identify the word:

- Visual: Looking at the first letters, word shape, letter clusters, visual alignment to other known words.

- Structure: Looking at the structure of the sentence to identify patterns, grammatical requirements, or other syntactic hints.

- Meaning: Looking for semantic hints, such as meaning of the sentence or prior sentences, context of the document so far, illustrations, and other hints that provide broader context.

Using these three-cues, new readers are taught to identify likely words, guess which is the best fitting, and if needed, to mentally replace the word with another that the reader knows.

This system is easier and faster to teach, and performs well in standardised tests where students can be prepared for a limited and consistent set of words that they need to know. However, it has problems. Very serious problems.

The system was based on a flawed understanding of cognitive development, and resulted in teaching students a system that allowed them to gain some understanding of written words quickly. Though the system also resulted in students often not understanding texts, and different students coming away with substantially different interpretations of the same text2. Those that learned to read with this method struggle to understand new words, and struggle with comprehension, due to replacing or skipping unknown words.

In 2020, one study showed that 75% of teachers in the US were teaching the three-cues method. However, this is changing as the issues with the method are becoming better known, and at least 12 states have now banned the method.

[…] the student told Dames that, at her public high school, she had never been required to read an entire book. She had been assigned excerpts, poetry, and news articles, but not a single book cover to cover. - The Elite College Students Who Can’t Read Books

As this method of teaching reading has spread, schools have also reduced the quantity of reading expected of students. Students are struggling to finish even simple reading assignments, struggling to understand what they read3, and become overwhelmed when asked to read lengthy or complex texts.

[…] we are in new territory when even highly motivated honors students struggle to grasp the basic argument of a 20-page article - Adam Kotsko

The simple version of all this is, unfortunately, teaching methods have failed to prepare children to read. Choices that were made over the last few decades are coming into full relief, and the picture is disturbing.

With the words “just setting up my twttr” Jack Dorsey started a revolution. Twitter was focused on short but high volume content, with a focus on interaction over quality. Micro-blogging was born. Short posts, drops in a firehose, most with a half-life measured in hours or even minutes4.

If you didn’t get a re-tweet or reply or like within the first few minutes, it was probably a miss. Might as well delete it and try something else to see if that one lands. The search for those tiny hits of dopamine started as soon as Twitter started.

Due to the small post size supported, thoughts had to be compressed, vocabulary limited to the shortest words available, commentary limited. Like the previous sentence, the posts were limited to 140 characters, a painful limitation that made clarity difficult and precision nearly impossible.

Then there was Instagram. Photos, just photos. A way to share filtered views of everyday life. The next step was Vine, a service that allowed users to view, create, and share 6-second looping videos. Tiny content, tiny dopamine hits.

From here, we all know how things have evolved. TikTok, Threads, Bluesky, Mastodon, and countless others.

The impacts of poor reading skills continue to compound as social media was reshaped to focus on shorter content, with compressed vocabularies, and an increased focus on achieving quick dopamine hits over meaningful communication.

If you include self-published books, it’s estimated that up to 4,000,000 books are published every year. Yet sales are often far worse than disappointing. A self-published author is likely to see 5 copies sold. For professionally published books, that number climbs to roughly 1,000.

[…] based on data on 58,000 books published in a year, ‘90% sold less than 2,000 copies, and 50% sold less than 12 copies.’ - The Elysian

While this isn’t to say that people have given up on books, as popular authors are still selling well, it does show that there is a massive disconnect between those writing books and the market that’s actually available5.

Given the sales figures that can be reasonably expected, writing a book is, sadly, often more about either passion or ego than viable income.

Blogging is alive and well and simultaneously a dead relic, it just depends on who you ask. There are now more than 600 million blogs, a number that has been growing rapidly. However, while the number of blogs is climbing, the authenticity is dropping. For those focused on company blogs, 57.4% are using AI to create content, and various studies show an intent to use AI more in the future. Studies show interest in blogs dropping, especially among young people, as early as 2010.

Estimates vary, though approximately 1.6B-2.5B blog posts are published every year. Yet, it’s also becoming harder to convince people to actually look at these posts: roughly 60% of Google searches result in no clicks, searches where the user either relies on an AI summary or what they saw on site previews. But that’s not the worst thing going on, it gets worse.

According to one source, the average reader only spends 52 seconds reading a blog post. The average blog post across the industry is roughly 1,400 words; at a normal reading speed, that means on average, a reader will cover about 150 words before leaving.

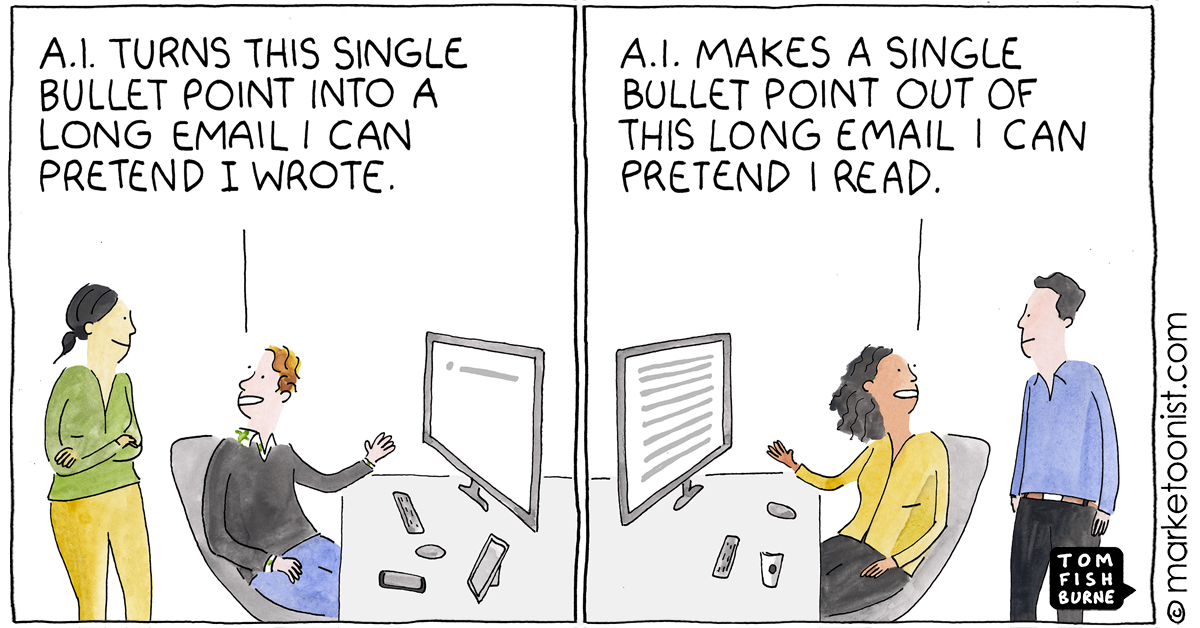

AI is everywhere, and it’s critical to this discussion as well. As noted above, 57.4% of corporate bloggers are using AI to draft content. Another, a survey of professional writers, show that 63% of writers use AI to generate text that they later edit. While some avoid using AI to generate content, including myself, the percentage is not high, and seems to be trending lower.

In the book market, the number of books that are all or largely AI generated is climbing rapidly. In one study of books available on Amazon, in a sampling of books in one category, 82% were found to likely be AI. A broader industry analysis put the number at 20% of all self-published books. The number of books generated by AI has grown to such an extent that Amazon now limits self-publishers to three new books per day.

Once we get through writing, we then land on the other side: AI summaries. A survey shows that 87% of adults in the US use AI summaries while searching, 60% use it to search for information, 48% use it to summarise long texts.

This can be combined with AI being integrated directly into browsers, or browsers being released by AI companies to offer deeper integration, making it easy to get an AI generated summary without even leaving the tab. Or email platforms integrating AI summaries. Or corporate chat platforms integrating AI summaries. Or meeting platforms integrating AI summaries. It keeps going. Anywhere there is long text, there’s an AI summary button within a few clicks.

At the beginning of this essay I asked the question, is long-form writing dead? At this point I think it’s clear that we’ve been asking the wrong question. There is a great deal of long-form writing in the world, and it’s quite possible that it’s growing (though the quality is increasingly questionable). The real question comes down to, is reading long-form content dying? Is it getting to the point that it’s pointless to write because it won’t be read?

That is a question that we will have to leave to the future, though I suspect, with what we have seen here, that there is reason to worry.

This article, for the sake of brevity, keeps the description brief and focused on how it applies to the points made herein. The issues with the three-cueing system are well documented and widely available. If you are unfamiliar with this system, I suggest that you research the issue and its history. From my experience as a person that learned phonics as a child and as a parent with children that were taught with three-cueing at school, and seeing the complications it has caused, I have strong opinions on this topic. ↩︎

A study asked a group of student volunteers to read the first 7 paragraphs of Bleak House by Charles Dickens. Subjects were asked to rewrite the passage in modern English, with free access to to dictionaries, reference material, and their phones. 58% were unable to understand the material to the point that they would be unable to read the novel alone. Only 5% were found to be proficient and properly understood the material. These students were English majors. See They Don’t Read Very Well: A Study of the Reading Comprehension Skills of English Majors at Two Midwestern Universities. See also Teaching with Whole Books Boosts Comprehension and Engagement for further reading; this article extensively documents the challenges with slipping reading comprehension. ↩︎

There are a variety of causes of reduced reading comprehension, and the use of flawed methods to teach new readers is just one. While I will explore this more, I should be clear that this can’t be entirely blamed on three-cueing. ↩︎

I talk more about the view of seeing online content in terms of its half-life in Write Like You Are Running Out of Time. I find this to be a particularly useful way to view the effective lifespan of what we write. ↩︎

Exact figures for the book industry are notoriously hard to find. Much of the data is treated as confidential, some publishers & platforms don’t share useful data, including Amazon, making it difficult to find consistent and well-sourced statistics. You will likely see somewhat different figures from different sources, so these should be seen as illustrative instead of exact. ↩︎