Since this was published, more detailed information has become available: analysis of the SSH backdoor, the VPN backdoor, and the cryptography of the VPN backdoor. If you want a more detailed understanding of what was done, please take a moment to read these pages.

The news is tearing through the information security community – Juniper seems to be on the lips of everyone now, let’s take a quick look at the information available:

Woah! Juniper discovers a backdoor to decrypt VPN traffic (and remote admin) has been inserted into their OS source https://t.co/vAywOclxLt

— the grugq (@thegrugq) December 17, 2015

This morning, Juniper Networks announced an out-of-cycle update for their ScreenOS firewall operating system (not the newer Junos) to patch two unrelated issues (both identified as CVE-2015-7755):

- Unauthorized remote administrative access

- VPN traffic decryption

The meat of the announcement is this one paragraph:

During a recent internal code review, Juniper discovered unauthorized code in ScreenOS that could allow a knowledgeable attacker to gain administrative access to NetScreen® devices and to decrypt VPN connections. Once we identified these vulnerabilities, we launched an investigation into the matter, and worked to develop and issue patched releases for the latest versions of ScreenOS.

I added emphasis to the most important part: code that wasn’t authorized was first released in September 2012, and only now discovered.

They provided very limited technical information; there is some detail on the unauthorized remote administrative access – the log, if not altered, will reveal that the backdoor has been used, as it will log that system connected over SSH instead of an actual user name.

This is the kind of log entry that you would expect in the case of a backdoor that was intentionally hidden – it could easily be looked over, it doesn’t immediately stand out. When designing a backdoor, keeping it subtle is key.

The second issue, decryption of VPN traffic, has no useful information – other than an attacker needs the ability to monitor the encrypted VPN traffic. What this means is that it would only be useful to an attacker that was able to monitor networks – so it would be of most value to nation-state level attackers.

For both vulnerabilities, they state that a knowledgeable attacker could do this – to me, that smacks of NOBUS, or nobody but us, a key strategy for NSA and similar attackers. Attacks that require the knowledge of some secret that couldn’t be easily learned, allowing them to take advantage of it, while keeping risks of others exploiting it as low as possible.

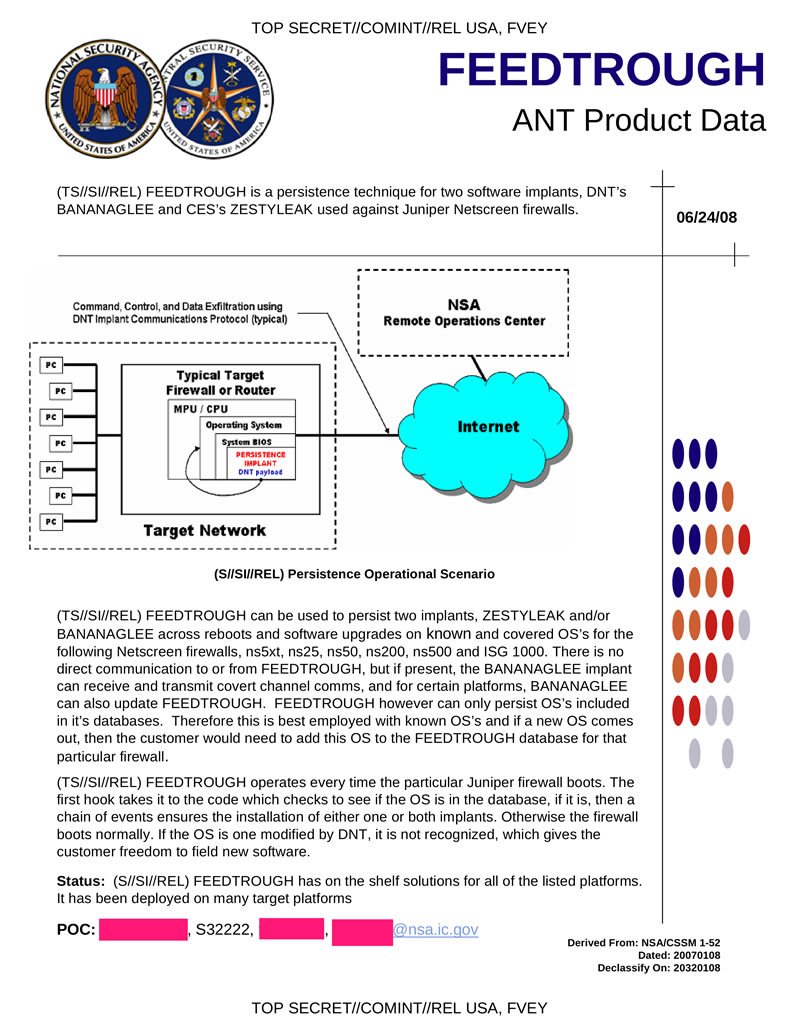

Some are speculating that this could be FEEDTHROUGH:

In the case of Juniper, the name of this particular digital lock pick is “FEEDTROUGH.” This malware burrows into Juniper firewalls and makes it possible to smuggle other NSA programs into mainframe computers. Thanks to FEEDTROUGH, these implants can, by design, even survive “across reboots and software upgrades.” In this way, US government spies can secure themselves a permanent presence in computer networks. The catalog states that FEEDTROUGH “has been deployed on many target platforms.”

Is this FEEDTHROUGH? Is this a backdoor to make it easier to install FEEDTHROUGH (interdiction can’t be cheap)? It’s hard to say – as is the case with many of the ANT documents, there simply isn’t enough details to tell if they are connected.

My hope when the story broke was that it was debugging code that was inserted into a production release, or something of that nature – at this point I’m losing hope. It’s exactly what an intentional backdoor would look like. We shouldn’t speculate too much, but this doesn’t look good.

While writing this, Dan Goodin published his article on this – go read it.

Update: HD Moore posted a list of the modified strings; a change caught my eye, and was pointed out soon after HD posted it. In the version where the backdoors were introduced, a constant was changed:

-2c55e5e45edf713dc43475effe8813a60326a64d9ba3d2e39cb639b0f3b0ad10

+9585320EEAF81044F20D55030A035B11BECE81C785E6C933E4A8A131F6578107

This changed was reverted in the fixed version, making it clear that this plays some role in the backdoor – as researched progressed, it was suggested that it was a custom y coordinate, or perhaps a public key.

At this point, it appears to be Dual EC DRBG, which has a documented history of being vulnerable to backdooring – at this point, it seems that may be what happened here. The patch by Juniper didn’t remove Dual EC DRBG, but revert the change to it. This makes a lot of sense, as this is a NOBUS backdoor – it requires knowledge of a secret to be able to exploit, which fits with the description that Juniper provided.

Research is still ongoing.