While testing ccsrch I noticed a number that looked familiar – my debit card number. Now, being just a little paranoid, I don’t leave such information on my system unencrypted – so seeing it was a real surprise. But, here’s the real kicker: it was on my work PC, where it never should have been. But there it was, plain as day, in clear text. I spent a couple of minutes staring at the log trying to figure out why it would be there.

Once I saw the file name, a sinking feeling set in and the answer became clear:

%LocalAppData%\Google\Chrome\User Data\Default\Sync Data\SyncData.sqlite3

So it turns out that it’s Chrome’s sync feature that was saving my information, but why?

It turns out that auto-fill data is synced with your Google account (if you’re signed in and have the feature enable, of course), and all of the computers you’re signed into – and by default, without the benefit of encryption. This file may contain any number of things, from mine I was able to extract the following:

- Full name

- Wife’s full name

- Date of birth

- Wife’s date of birth

- Social Security Number

- Multiple credit card numbers

- Multiple CVVs

- Bank account & routing number

Not to mention quite a few websites I’ve been to, various addresses, employer’s name and other various useful tidbits. All would be quite useful for identity theft or highly targeted spear phishing.

Now am I saying that syncing auto-fill is bad? No, not at all. It’s a very useful time saver, but what takes it from a useful feature to security issue is the fact that by default, this data isn’t encrypted!

What are the risks?

There are three significant risks I see here:

1). Disclosure to less trusted systems:

In my case, I trust my laptop to be secure; between full-disk encryption (via TrueCrypt) and other precautions, I know that I don’t have too much to worry about. On the other hard, my Work PC is on a corporate domain, and at least a couple dozen people have permissions sufficient to access my personal files – thus I don’t trust anything too valuable on it.

Now because of the fact that this feature is insecure by default, that data is exposed to a less trusted system.

It can also go the other way: a number of auto-fill entries on my personal laptop were from forms on internal-only applications that only my Work PC would be able to access. So this means that anything sensitive could be leaked to home networks which are typically less secure than corporate environments. If you routinely handle PCI, HIPAA, or other restricted information – this type of leak could be a major issue.

2). Spear Phishing:

Let’s imagine a scenario:

You work for a defense contractor and I work for a foreign intelligence agency. Through some targeted attacks I manage to penetrate your home network, but have been unable to make it into your corporate network. I grab the sync database file from your home PC and extract one of your credit card numbers. I look up the IIN and find out what bank the card is from. Once I have this, I build a PDF with the latest 0day exploit, and send it with a convincing subject line:

“Important Information about your Bank of America credit card ending in 7850”

Normally you’d dismiss it as spam, but the last four digits are right – so you open it, just in case. The exploit kicks in. I’m in, you’re done.

This is just a simple and quite contrived example, but you get the idea.

3). Google Data Mining:

This is the most paranoid and least likely, but given Google’s issues in controlling their people – I’d say not impossible (see here, here, and here).

Just for a moment, think about the fact that Google has the following:

- Your account data (name, email, etc.)

- Your auto-fill history (see the list of items I found above)

- Tons of data from their other services

- At least parts of your browsing history, if not much of it

- Engineers that truly enjoy data mining

Most other companies I wouldn’t worry about; but knowing the people who Google hires, and the skill they have in manipulating data – you know that some engineer is using his 20% time to do this (or at least is wishing he could).

If nothing else, I know if I worked at Google – playing with this data would be tons of fun. 😉

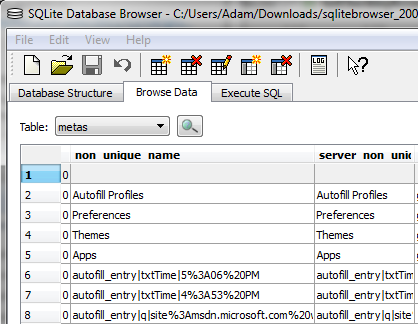

Want to see your data?

To see what Chrome has saved about you, download SQLite Browser, and open the file I mentioned above. Go to the “Browse Data” tab, and select the “metas” table. What you’re looking for is in the “non_unique_name” column (among other places). You should see something like this:

The entries starting with “autofill_entry” are the ones you are interested in, but you’ll likely find some of the other records interesting as well. If you see the word “encrypted” then your data is already encrypted, and you don’t have to worry about this.

Is this a vulnerability in Chrome?

No, not at all – though it was a mistake. They should encrypt everything by default, and not provide an option to do otherwise. There’s no reason to expose users to a potential security risk when there’s a simple fix. Security isn’t something users should have to opt-in to; and unless there’s a very good reason, they shouldn’t have a way to opt-out.

Google should understand security and the value of the data they hold; they should be more responsible for the data (and faith) people give them.

How do I fix it?

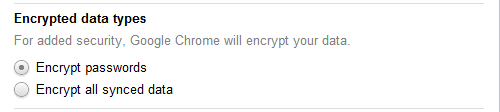

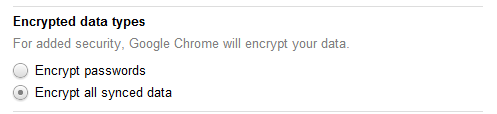

Simple, from the “wrench” menu, select Options -> Personal Stuff -> Sign In -> Advanced… and then under “Encrypted data types” select “Encrypt all synced data” – and that’s it. After a couple of minutes the entries that were visible before will now just display the word “encrypted.”

You can also go a step further, and get rid of this data by disabling auto-fill to ensure that potentially sensitive information isn’t being persisted when it shouldn’t be.